This autumn, the UK House of Commons’s Business and Trade Committee issued a call for evidence, asking UK citizens, companies and organisations for guidance on outlining the committee’s priorities for 2026. Recognising the opportunity Parliament has to empower growth for deep-tech scaleups and advanced-material manufacturers like Paragraf, we were grateful to be able to contribute the below response to that call.

Introduction to Paragraf

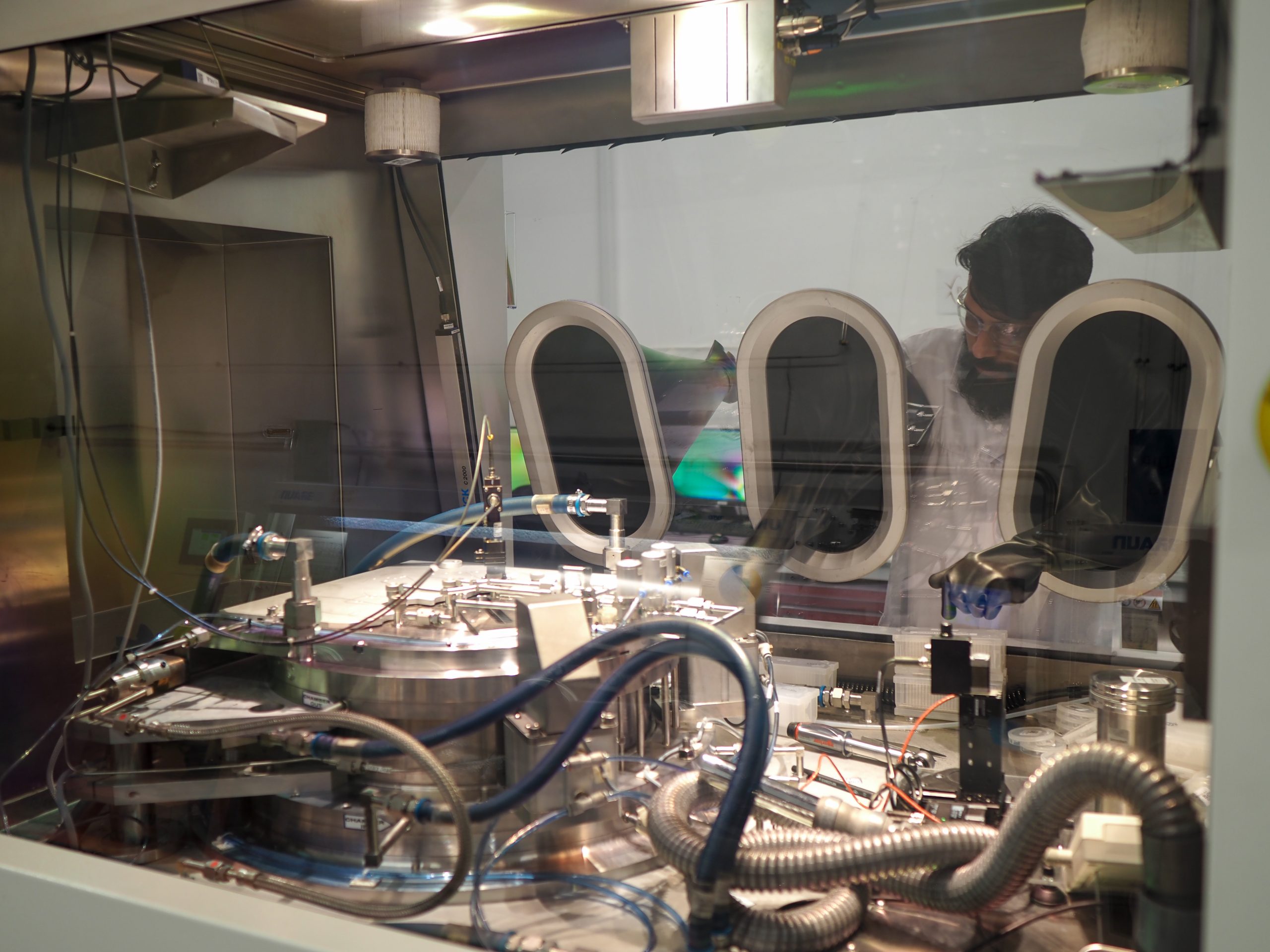

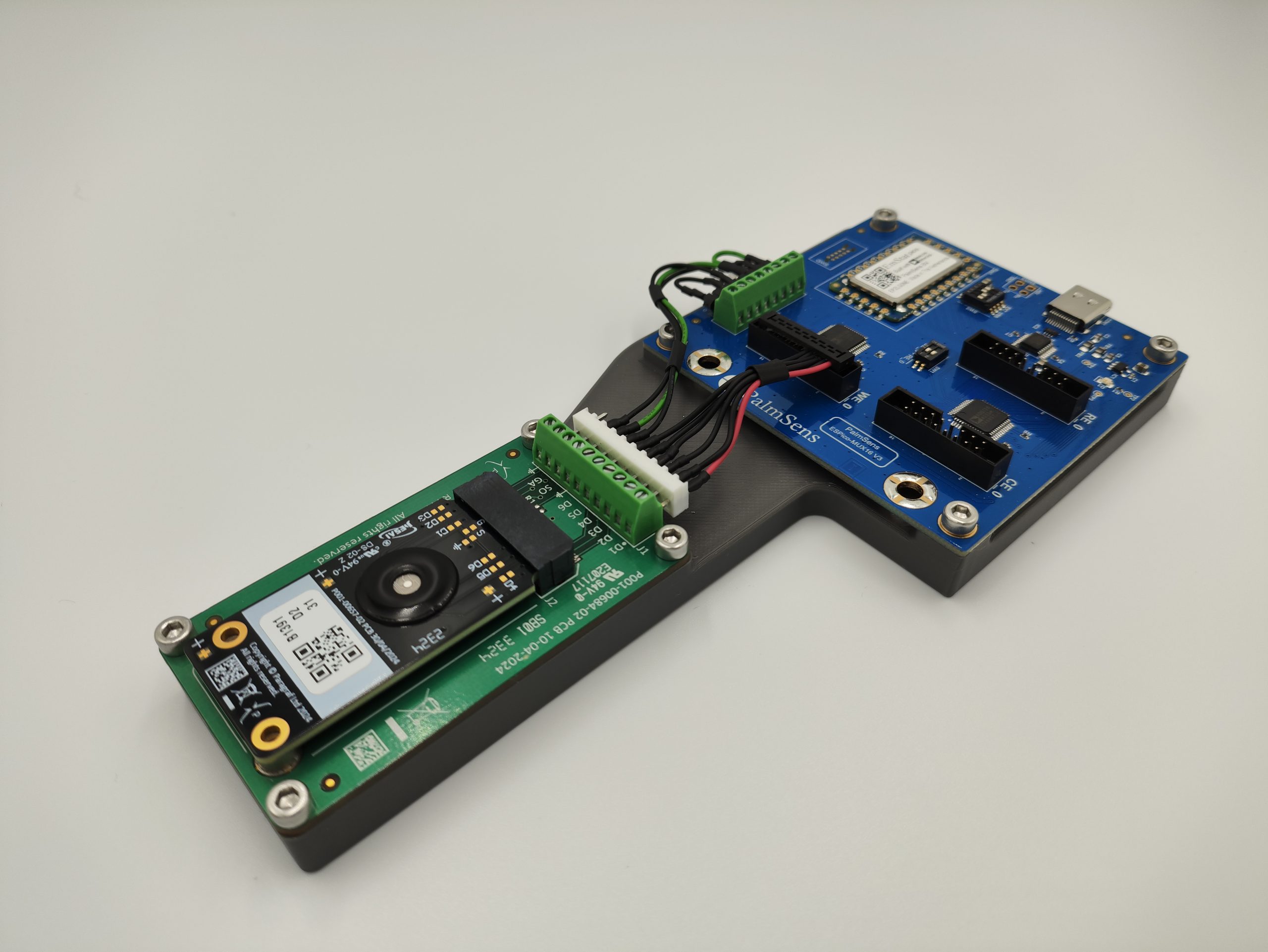

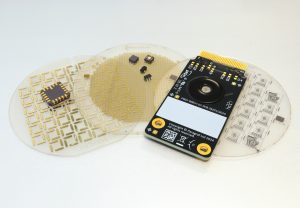

Paragraf, a Cambridgeshire-based deep-tech company, is the world’s first manufacturer of graphene-based electronic devices at commercial scale using standard semiconductor processes. Spun out from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Materials Science in 2018, we currently have ~110 employees across facilities in Somersham and Huntingdon, in Cambridgeshire, and in San Diego, California. We have raised >£100m from leading investors including New Science Ventures, Parkwalk, Amadeus Capital Partners, Mubadala and British Patient Capital.

Our graphene field-effect transistors and graphene Hall sensors serve critical applications in healthcare diagnostics, quantum computing, aerospace and industrial automation. We are contributing to this inquiry because our experience navigating the challenges of scaling deep-tech manufacturing in the UK provides keen insight into the barriers and opportunities for business growth, investment confidence and productivity enhancement. As a company at the intersection of advanced materials science and commercial manufacturing, we represent the type of high-value, innovation-led enterprise that the Industrial Strategy (IS) seeks to support.

Business Confidence

Investor confidence in deep-tech manufacturing depends on policy stability and long-term commitment to strategic sectors. Our industry requires sustained investment over 10-15 year horizons. Frequent policy reversals undermine confidence and make long-term capital commitments difficult to justify.

Access to patient capital specifically tailored to deep-tech has been essential to our growth. Traditional venture capital models fail to accommodate the longer development timelines and capital intensity of advanced manufacturing. British Patient Capital’s Future Fund demonstrates the value of government-backed patient capital supporting R&D-intensive companies.

The availability of skilled technical talent in advanced materials, semiconductor processes and precision engineering directly impacts our ability to scale. The UK’s university system provides excellent graduate talent, but availability is vulnerable to countries offering more attractive visa arrangements and lower personal tax burdens. Infrastructure for advanced manufacturing, including cleanroom facilities, semiconductor fabrication equipment, and reliable, affordable energy, determines where we can viably scale operations. Gaps remain compared to international competitors.

The IS’s focus on eight growth-driving sectors provides welcome clarity. A coherent framework recognising advanced manufacturing as integral to UK economic growth helps us articulate our value proposition; however, communication channels remain fragmented. Large corporates have clear routes to influence policy while scale-ups often lack direct engagement mechanisms. The IS Council must allow emerging technology sectors similar access to established industries.

Engagement with the investment community has improved, but fundamental mismatches in understanding deep-tech risk profiles remain. The City favours software and asset-light investments over capital-intensive manufacturing. Government could help educate institutional investors about the strategic importance and long-term returns from backing advanced manufacturing.

The 10-year IS commitment with statutory backing through the IS Council is significant. Its credibility rests on consistent implementation across government and resilience to political cycles. Recent announcements on R&D tax relief changes, corporation tax rates and employment costs have created uncertainty making comparative assessment with alternative locations more challenging. Long-term planning is essential for supply chain development, requiring coordination across multiple companies all needing confidence in sustained demand and policy support.

Pro-Growth Reforms and Investment

Skills development is the most urgent constraint. The UK faces critical shortages of technicians and engineers trained in advanced manufacturing processes, semiconductor fabrication and materials science. Universities produce excellent researchers but insufficient focus on practical, industry-relevant skills for manufacturing roles forces substantial investment in internal training that delays time to productivity. Government and industry should co-develop targeted training in growth-driving sectors.

Planning reform creates delays and uncertainty making the UK uncompetitive for time-sensitive investment decisions. Our expansion timelines have been impacted by planning delays. Streamlined processes for designated IS sectors, particularly within IS Zones, would significantly improve investor confidence.

Infrastructure requires sustained attention. Energy costs for manufacturing are significantly higher in the UK than competing jurisdictions, directly impacting our cost base. Swift reduction in electricity costs for high-usage manufacturers and improved grid connection access would remove major bottlenecks.

Regulatory reform should enable innovation while maintaining necessary standards. For emerging technologies like graphene-based electronics, frameworks developed for traditional materials may not be fit for purpose. More agile, science-based regulatory approaches can better keep pace with technological development.

The IS will be transformative with sustained commitment and adequate resourcing. The emphasis on sectoral planning, with £4.3 billion funding commitment and targets supporting advanced materials, directly benefits companies like ours; however, driving growth requires tangible policy changes reducing costs and friction. Announcements without rapid implementation risk the strategy becoming another document rather than a delivery mechanism.

Support must reach scaling companies, not just established large firms or very early-stage startups. Currently, research funding, innovation support and commercial scale-up exist in separate silos. Companies integrating into the marketplace often fall between available support mechanisms.

Translating growth into higher productivity and living standards requires investment in skills and training in regional locations. High-value manufacturing creates well-paid jobs not requiring relocation to expensive city centres. Our Cambridgeshire facilities employ skilled technicians, engineers and scientists in roles paying well above regional averages. Supply chain development creates multiplier effects when we source from UK suppliers. Government procurement policy should prioritise building domestic capability in strategic sectors.

Costs of Doing Business

The cumulative cost burden has increased significantly, impacting our competitiveness relative to international alternatives. While individual measures may be justified in isolation, the combined effect creates a challenging environment for capital-intensive businesses.

The increase in employer National Insurance (NI) contributions directly increases our cost base by hundreds of thousands of pounds annually, materially impacting hiring plans and investment capacity. The reduction in the secondary threshold exacerbates this. Companies like ours compete globally for talent and investment; cost increases not matched by competitors make the UK less attractive.

As an electricity-intensive manufacturer, we face energy costs substantially higher than competitors in other countries. The IS commitment to reduce electricity costs for high-usage manufacturers in the is essential and must be implemented urgently. Delays extend competitive disadvantage.

R&D tax relief evolution has been inconsistent, making long-term R&D planning difficult. The merged RDEC scheme must genuinely incentivise R&D investment, not simply reduce costs of existing activity. Regulatory compliance costs have increased, particularly around employment law, data protection and sector-specific regulations. Mid-sized companies lack large compliance departments but face similar requirements to corporates. Regulations that are scaled by company size would alleviate burdens.

Corporation tax increases significantly impact decisions about where to locate IP, manufacturing or headquarters. Rather than broad-based cuts, government should consider targeted measures for growth-driving sectors and scaling companies: employment cost relief for companies in IS sectors through reduced employer NI for highly skilled technical roles or growth-linked relief; accelerated capital allowances for investment in manufacturing equipment and R&D facilities; energy cost support for qualifying manufacturers as committed in the IS; enhanced R&D tax relief for advanced manufacturing recognising higher capital intensity and longer development cycles; regulatory relief including streamlined compliance for certified companies and reduced reporting frequency for mid-sized businesses; and skills investment tax credits incentivising training programmes addressing strategic skills gaps.

These measures should be revenue-neutral or revenue-positive over the medium term by driving growth, increasing employment, attracting investment and improving productivity. The fiscal cost of not supporting growth sectors is ultimately higher.

Recent budgets demonstrate several lessons:

- Policy consistency matters more than individual measures.

- Frequent changes create uncertainty discouraging investment. Businesses need stable frameworks more than optimal rates.

- The recent employer NI increase impacts scaling companies disproportionately because we are employment-intensive and increasing payroll rapidly.

- Announcing significant cost increases shortly after launching an IS creates cognitive dissonance.

- Trade-offs should be explicit and international competitiveness must be central.

- Every policy should be stress-tested: does this make the UK more competitive for investment or less?

Budgets should be evaluated against IS objectives with clear impact assessments on growth-driving sectors.

Productivity Growth

The UK’s productivity gap stems from insufficient business investment as a share of GDP, partly due to policy instability making long-term investment riskier, partly due to higher capital costs and structural factors favouring asset-light models. Technology diffusion from frontier firms to the broader economy is weak. The UK has world-class research and innovative companies, but mainstream business adoption of advanced technologies lags. Skills gaps prevent productivity-enhancing investment from delivering potential. Regulatory and administrative burdens consume resources that could be deployed productively. Inadequate physical and digital infrastructure (e.g., slow planning, grid connection delays, poor transport connectivity) reduces output per worker. Low R&D intensity outside a few sectors means most businesses are not systematically innovating to improve productivity.

Improving productivity in growth-driving sectors requires genuine partnership. For instance:

- Sector councils of leading businesses, researchers and policymakers should have authority to influence policy, not be purely consultative.

- Shared productivity targets with agreed metrics would enable tracking and accountability.

- Co-investment in enabling infrastructure such as shared testing facilities, specialised training centres and supply chain development would build productivity foundations.

- Regulatory sandboxes would enable productivity-enhancing innovation without disproportionate compliance costs.

- Procurement policy should prioritise UK suppliers in strategic sectors, providing stable demand enabling productivity investment.

- Data sharing and benchmarking programmes would enable businesses to identify productivity gaps and learn from best practices.

- Joint R&D programmes should explicitly target productivity challenges, not just new products.

Technology, skills and innovation policy are interdependent and must be addressed holistically. Adoption should be prioritised as much as invention, supporting diffusion through demonstration projects, adoption grants and knowledge transfer programmes. Skills policy must shift from reactive to anticipatory, developing skills for emerging technologies through industry-education collaboration. Apprenticeships and technical education should have parity of esteem with university education. Innovation policy should support process innovation and productivity improvement, not just new products. R&D incentives should explicitly recognise manufacturing innovation.

Fair sharing of productivity gains requires deliberate policy choices. Employment standards in growth-driving sectors should set high benchmarks including fair pay, career development and profit-sharing. Regional distribution of productivity-enhancing investment ensures gains are not concentrated in prosperous areas. Manufacturing can locate anywhere with appropriate infrastructure; IS Zones should prioritise areas with lower current productivity. Supply chain participation spreads productivity gains when leading companies work with domestic suppliers to improve their processes. Skills development accessible to workers of different backgrounds ensures productivity gains translate into wage gains. Tax policy should ensure productivity gains benefit public finances, enabling investment in public services and infrastructure supporting broader living standards.

The Role of Regions and Cities

Regional leaders understand local economic strengths and constraints better than central government. Empowering them requires genuine devolution of resources and decision-making. Multi-year funding settlements for growth initiatives would enable strategic planning. Control over skills spending would enable regions to develop training programmes aligned with local industrial strategy. Genuine planning devolution would give IS Zones expedited, locally controlled planning processes. The Office for Investment should support regional leaders in leveraging local relationships to attract appropriate investment. Coordination mechanisms between local authorities should reflect economic footprints spanning multiple local authority areas. Empowerment must be balanced with accountability through clear performance metrics tied to productivity, employment and investment outcomes.

Housebuilding and infrastructure investment can be transformative if delivered strategically. Housing supply in areas with strong employment growth enables companies to attract and retain workers. Transport infrastructure connecting residential areas to employment sites enables labour market participation. All IS Zones should have world-class digital connectivity. Energy infrastructure directly impacts manufacturing competitiveness; infrastructure investment should prioritise areas designated for industrial growth. Skills infrastructure should be co-located with industrial development. Infrastructure investment should follow IS priorities rather than proceeding independently.

International examples provide valuable lessons:

- Germany’s Fraunhofer Institutes demonstrate how distributed research excellence supports regional industrial clusters.

- South Korea’s regional innovation strategy shows how targeted investment in specific technological capabilities creates regional specialisms.

- Singapore’s Skills Future programme demonstrates how proactive skills development can anticipate economic change.

- Taiwan’s science parks show how co-location of research, manufacturing and supply chain creates productivity benefits.

- Netherlands’ Brainport Eindhoven demonstrates how public-private partnerships drive regional transformation.

Common themes are long-term commitment, coordination between stakeholders and focus on specific competitive advantages.

Better Regulation

Some regulations are necessary and provide confidence; others create disproportionate burden without commensurate benefit.

Safety and environmental regulations are appropriate and important, though compliance processes could be streamlined for low-risk companies with good track records.

Employment regulations have increased significantly in complexity and cost, making hiring more expensive and risky.

Planning regulations result in long, unpredictable processes making it difficult to execute growth plans confidently.

Financial regulations create barriers for growth companies accessing capital; requirements designed for large corporates impose disproportionate costs on SMEs.

Product regulations for emerging technologies are often unclear because frameworks were developed for traditional materials.

Data and privacy regulations impose significant compliance costs; post-Brexit freedoms could result in regimes maintaining high standards while reducing administrative burden. The fundamental issue is that regulation has accumulated without systematic review of cumulative impact.

The commitment to reduce regulatory burdens by 25 percent is welcome, but success depends on implementation. Scope matters. Removing trivial reporting requirements while leaving major burdens untouched provides little benefit. The review should prioritise areas where businesses identify greatest friction.

Process reform is as important as rule changes. Digitising reporting, reducing frequency and accepting more flexible evidence would help significantly. Regulatory consolidation is needed; multiple regulators with overlapping jurisdiction create confusion and duplicated work. Risk-based approaches should expand so companies with strong compliance records face lighter-touch oversight. Sunset clauses on regulations would force systematic review and prevent accumulation of outdated requirements. The Regulatory Action Plan should involve genuine consultation with growing companies experiencing regulation most acutely.

Regulatory consolidation could significantly improve efficiency. A single business regulator for various standards would provide one point of contact rather than multiple agencies with overlapping jurisdiction. Sectoral regulators for IS growth-driving sectors could provide specialist expertise and coordinated oversight. Digital platforms enabling businesses to report once to government with data shared between relevant agencies would eliminate duplicated reporting. Regulatory hubs in IS Zones could provide integrated support with co-located regulators working collaboratively. International regulatory alignment could reduce burden for companies operating across borders through mutual recognition agreements. Some technical areas require specialist regulatory expertise; the goal should be better coordination, not necessarily fewer agencies.

Risks and International Context

The relationship with the EU is critical. As our largest trading partner, frictionless trade directly impacts competitiveness. Closer economic cooperation and simplified trade processes are essential. Regulatory alignment in key areas would reduce compliance costs without compromising UK autonomy through mutual recognition agreements for products and standards.

US competition is intensifying. The UK cannot match US subsidy levels but can compete through a stable regulatory environment, strong research base and access to European markets. The UK-US Tech Prosperity Agreement provides a framework for collaboration rather than pure competition.

China’s position as both customer and competitor requires sophisticated strategy. We should focus on technologies where IP protection and advanced capabilities matter. Supply chain resilience concerns are driving diversification from China, creating opportunities for UK manufacturing.

Emerging economies offer partnership opportunities. India’s technical talent and UK’s research excellence are complementary.

The UK’s optimal position is as a bridge between the US and EU, leveraging strong research capabilities, legal system and time zone to serve as the location of choice for companies needing European market access with UK business environment benefits. For deep tech, this means being the place where new technologies are invented and initially commercialised before scaling globally.

Differentiation, not replication should guide strategy. We cannot out-subsidise the US or out-cost Asia. We must out-innovate and out-specialise, focusing on technologies where UK research leadership translates to commercial advantage.

Government Strategy and Coordination

The IS provides welcome strategic coherence that has been missing. Clear sectoral focus enables coordination across government departments around shared objectives. The IS Council should improve coordination and accountability; effectiveness will depend on its authority and resource. Departmental silos remain problematic. Policies on skills, innovation, infrastructure and business support should avoid working at cross-purposes or leaving gaps between departmental responsibilities. Regional coordination between national IS and local growth plans is underdeveloped; alignment between central commitments and regional delivery needs strengthening. Cross-cutting issues such as planning and regulation affect multiple departments but lack clear ownership, leading to slow progress on systemic reforms. Delivery mechanisms are fragmented; Innovate UK, British Business Bank, Catapults and numerous other bodies have overlapping remissions. Streamlined delivery with clear accountability would improve effectiveness. Ministerial stability will be critical to sustained implementation. High ministerial turnover has historically undermined long-term industrial policy. The 10-year commitment requires corresponding political commitment.

Implementation of the IS should include a dedicated delivery unit with authority across departments and direct reporting to the Prime Minister.

Conclusion

The UK has a genuine opportunity to drive sustainable growth through strategic sectors like advanced manufacturing. Paragraf’s experience demonstrates both the potential and the challenges. We have grown rapidly, raised significant capital and begun bringing genuinely world-leading technology to market from a UK base. However, we face increasing competitive pressure from countries that are more systematically supportive of deep-tech manufacturing.

The IS provides the right framework, but implementation must be rapid, sustained and comprehensive. This requires reducing costs and friction for businesses, investing in enabling infrastructure and skills, maintaining policy stability, and ensuring that growth sectors genuinely benefit from focused support.

The UK’s research excellence is a unique advantage that creates opportunities in emerging technologies. Converting this into scaled commercial success requires a business environment that enables rather than inhibits growth. With the right policy choices, the UK can become the natural location for companies bringing transformative technologies from laboratory to market. The prize—high-value jobs, improved productivity, and enhanced living standards across the country—justifies sustained commitment to making this happen.